Crossposted from Adventures in Poor Taste

Pink galaxy at morning, starship take warning. Pink galaxy at night, starship’s delight.

Is Star Trek’s Galactic Barrier Real?

(No, but there’s some weird stuff out there)

Star Trek: Discovery comes to an end this year, after a run that successfully rescued the franchise from the clutches of J.J. Abrams’ two-dimensional alternate universe movies and brought it back to television, where it belongs. While views of the show are mixed, there’s no doubt that Discovery made brave choices and ultimately reignited the current era of boundless Trek. It brought an enthusiasm for science, with a litany of new concepts, a character named for a mushroom researcher, and an irrepressible ensign who’d say things like, “I f*cking love math!” For all its many invented technologies, Star Trek has been relatively faithful to scientific reality — in spirit, if not in details.

The science fictional elements are typically grounded in at least some speculative ideas about nature, or relate to a concept that scientists would recognize. This doesn’t mean that things like matter-transporting and faster than light travel are actually possible, but understanding they’re not, the creators of the shows typically build in explanations. The abrupt ship maneuvers that would flatten the crew as a starship accelerates? Inertial dampeners. Quantum indeterminacy impeding the ability of the transporter to precisely image an object? Heisenberg compensators. Someone to cook disgusting food, endanger the crew with pointless detours, and date a 2-year-old? Neelix.

One area where Star Trek series have tended to stumble is with actual astronomical phenomena. Many of the interest points in the shows have to do with fictitious yet frequent anomalies that could never do what they’re depicted doing. “Subspace temporal vortexes,” “quantum folds,” and “warp bubbles” are fine and all, but astronomy has plenty of weird, speculative stuff already! Quark stars, cosmic strings, magnetic monopoles, several types of supernovae, black hole collisions. Admittedly, writers do have to come up with about 26 episodes a season, but it’s always felt as if they’ve never come close to exhausting the smorgasbord of real or near-real phenomena that astrophysics has to offer.

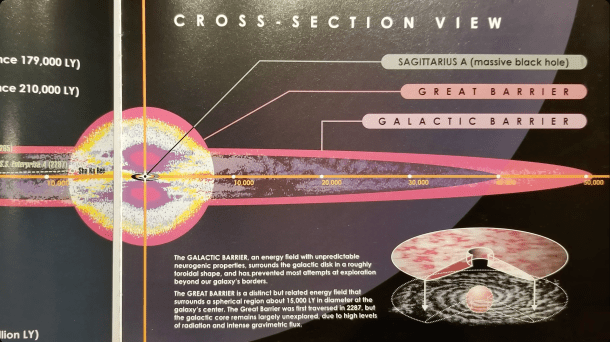

There is even one recurring structure which has been used repeatedly, despite being the opposite of a real astronomical feature — the Galactic Barrier.

Star Trek is set entirely within our galaxy, the Milky Way; a stage that gives the franchise at least 100 billion star systems to work with. For scale, Voyager, stranded on the far side, is 70 years from home at top speed. The fictional Galactic Barrier is a region enveloping either the rim or the entire exterior of the Milky Way. It may also dip down into the core to surround the disappointing God-planet in Star Trek V. It supposedly consists of “negative energy,” which can damage ships and has the counterintuitive property of being invisible from far away and bright purple as it’s approached.

As you might guess, there’s nothing like this in our galaxy. The Milky Way, shaped like a pancake of stars, gas, and dust 90,000 light years across, with a slight bulge in the center, has the rather pedestrian quality of petering out in density as you leave the disk in any direction. The edges get increasingly diffuse. (However empty and diffuse you think space is, it is far more empty and diffuse than we can possibly comprehend.)

But that’s not the whole story! Past the visible edge of our galaxy (and others) extends a halo of dark matter. We know this because the speed with which stars orbit the center of the galaxy does not decrease as you go outward in the disk. If only the visible matter of stars and gas were present, it would. In that gravitational discrepancy, invisible matter is hiding. Dark matter, as far as we currently know, is a type of massive particle which doesn’t interact electromagnetically. This is why it doesn’t emit light.

For that reason, dark matter doesn’t form bonds like those holding regular atoms and molecules together, nor does it undergo the friction-like breaking interactions that would make it shed energy and slow down enough to coalesce into stars or nebulae. Having not given up energy as luminous matter does, it distributes itself (approximately) within a spherical clump around the galaxy’s center of mass and extends out far beyond the stars, gas, and dust we see.

That is not how Star Trek‘s Galactic Barrier works. In the shows, the ship comes upon it suddenly, and it presents itself as sort of a glowy, purple cloud wall that only becomes visible within a light year or less. Spock’s analysis describes it as, “Density negative. Radiation negative. Energy negative.” Of course, neither density nor radiation can be “negative,” since they describe physical quantities, but I suppose that’s part of the mysteriousness. Ships trying to pass through this region suffer a widely inconsistent set of phenomena, belying its inconsistent amount of danger.

The barrier first appears in the Star Trek original series episode “Where No Man Has Gone Before” (AKA “the Gary Mitchell episode”). After finding wreckage from a ship lost to the barrier 200 years previously, the crew resolves to fly the Enterprise into it out of curiosity, to see if anti-galactic barrier technology has improved. They expect damage, and after some consoles explode and it’s casually reported that nine crew members died, the real weirdness begins. The Galactic Barrier turns Mitchell into a psychokinetic spooky man. Needless to say, this is not astronomically accurate.

Discovery confronts the edge of the galaxy, after a color palate reboot

We next see the Galactic Barrier in “By Any Other Name,” in which Kelvans from Andromeda travel to our galaxy on generation ships. The barrier has wrecked their vessels, forcing them to escape on lifepods, and they hijack the Enterprise to return home. Despite the fact that the edge of our galaxy is clearly transparent, they claim that they can’t get a message through it, so flying back is their only chance. Though they never say whether they modified the Enterprise, everyone gets through without much fuss, and it seems odd that the Kelvans’ seemingly more-advanced technology had a problem with it in the first place.

The crew sees it once more in “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” and they pass through it without any trouble, only to be “stranded” in the void outside the galaxy, without any reference points to navigate by. Considering that this thing is supposed to be invisible, that doesn’t make a lot of sense. Can’t they just look back over their shoulders at the galaxy behind them? By the final original series encounter with this force field, which is called the “Great Barrier around the center of the Milky Way” in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, it barely attempts to live up to its reputation — the Enterprise passes through it easily.

This would have been a great point to leave this silly concept behind. Subsequent series don’t mention the barrier, and actually hint that people are exploring extragalactic space or traveling to the Small Magellanic Cloud (a dwarf galaxy near our own). But after a nearly 40 year absence, the crew of Star Trek: Discovery brings it back in season 4, with another overhyped journey through the barrier, to reach the homeland of the season’s adversary. Even this show’s earnest ethos of “science is great!” couldn’t resist the appeal of resurrecting a baffling impossibility.

Star Trek is “about” many things, but perhaps most essentially, roaming the galaxy gives the crew the chance to encounter a wide diversity of life and cultures, all new to them. The distances may technically be astronomical, but on Trek, the cosmos is teeming with life and activity. The diplomacy between the Federation, the planets within it, and the brave new worlds it forges relationships with often mirror conflicts seen in our present day, and analogize social issues that we 21st century Earthlings contend with. As often as the stories feature a point of alienness, they resolve through cooperation across those differences.

So maybe putting a wall around the galaxy – foreboding, but not impermeable – is a reminder that for all the differences across our worlds, these civilizations share a place. An area removed from their interstellar neighborhood exists, and some unknown force is reminding the crew not to stray too far from the light of home stars. Moving toward total isolation and setting yourself apart is an action that damages and changes you. But the appearance of the Galactic Barrier is an illusion that can be surmounted by strong desire. The frontier stops at the coast, even though there’s an ocean to cross beyond, and worlds anew on the other side.

Or maybe the creators of Star Trek had a swirling pink cloud effect on hand back in 1966, and they wanted to throw around a neat-o phrase like “galactic barrier,” and they’d fill in the details later.

A physicist wanting to make an impact on the field most often imagines his or her name attached to an Equation, or a Theory. Or even, if they really want to move mountains, a Law. I have no idea what mathematicians think about, but I would assume that they are hoping to come up with Theorems and Conjectures. Of course, not everyone is an Einstein or a Kepler, able to remake a subject and declare a Law. But if you carve out a niche for yourself, or invent a novel way of dealing with a certain topic, you’re virtually assured of getting something. For an elegant discovery, you could have an Angle named after you, or a Number. Or in a more bizarre direction, a Sea or Paradox. de Sitter has an entire Universe! Me? If I could become the first person since Isaac Newton with an eponymous Bucket I would consider myself a success. There are so many strange things you could find named in your honor that I have compiled an extensive list of them with some examples namesakes on the right-hand side.

A physicist wanting to make an impact on the field most often imagines his or her name attached to an Equation, or a Theory. Or even, if they really want to move mountains, a Law. I have no idea what mathematicians think about, but I would assume that they are hoping to come up with Theorems and Conjectures. Of course, not everyone is an Einstein or a Kepler, able to remake a subject and declare a Law. But if you carve out a niche for yourself, or invent a novel way of dealing with a certain topic, you’re virtually assured of getting something. For an elegant discovery, you could have an Angle named after you, or a Number. Or in a more bizarre direction, a Sea or Paradox. de Sitter has an entire Universe! Me? If I could become the first person since Isaac Newton with an eponymous Bucket I would consider myself a success. There are so many strange things you could find named in your honor that I have compiled an extensive list of them with some examples namesakes on the right-hand side.